Inside the Vault: Vinegar Syndrome

At the core of the AMBA archivist’s job is the care of our area’s historical records, making sure that they last well into the future. This job is made up of many moving parts. In due time, we will explore all of these activities in this blog series, but today we are talking about a very important one: preservation.

Preservation can refer to many different things. One of the most important is environmental control, which means keeping records at an ideal temperature and humidity level, monitoring them for mould and signs of pests, and covering fragile items. It also includes remedial work like conservation or restoration, for those records that are already degraded by time and their storage environment. In general, these steps can be planned and completed in an orderly way. Sometimes, however, something urgent comes up and demands action.

At the AMBA, the most recent intrusion came in the form of an all-too-familiar smell. Harmless in the kitchen but alarming in the archives, vinegar is not a scent you want coming out of a box when you open it! When our summer intern, Marc-Alexandre Webb, was uploading some already-digitized images from the Normand Babineau Photography Collection, he opened a box and caught a whiff, prompting us to intervene.

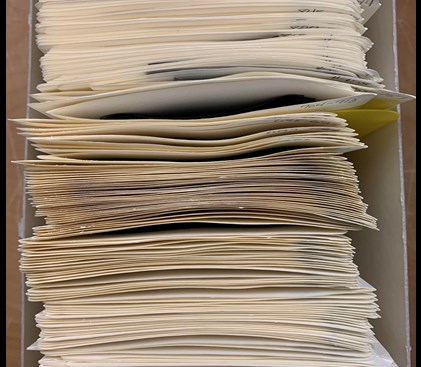

The Normand Babineau Photography Collection box from above, showing some warping of the negatives due to vinegar syndrome.

The scent of vinegar around photographic negatives and film reels points to a form of decay aptly named vinegar syndrome. Once the smell is noticeable, the syndrome has taken hold and it’s sometimes too late to be slowed or reversed. Film and negatives that are made of cellulose acetate are the culprits. The National Film Preservation Foundation states that, “The symptoms of vinegar syndrome are a pungent vinegar smell (hence the name), followed eventually by shrinkage, embrittlement, and buckling of the gelatin emulsion. Storage in warm and humid conditions greatly accelerates the onset of decay. Once it begins in earnest, the remaining life of the film is short because the process speeds up as it goes along. Early diagnosis and cold, moderately dry storage are the most effective defenses.”

At the AMBA, great care is taken to make sure that the vault temperature never rises above 20 degrees celsius, and the relative humidity remains stable at about 45%. Cold storage rooms (almost like walk-in fridges) with controlled humidity are best practices in an ideal world, but an archives like ours without an unlimited budget and space cannot meet this standard. The fact that this collection was stored in the vault since 2005 has likely slowed down the process of decay considerably.

Many of the sources we consulted recommend digitization of the negatives in order to capture them before any more degradation can occur. Luckily, we were able to extend Marc’s time with us in order to digitize all of the images now that we've caught it at an early stage.

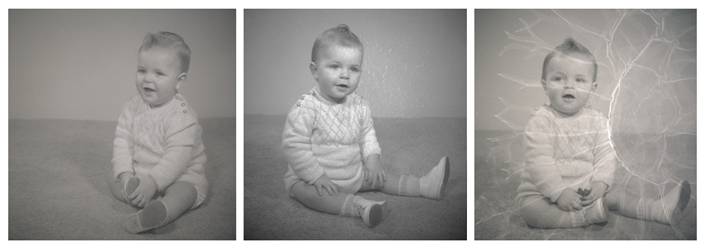

Three photographs from the same photoshoot were stored side-by-side. From left, the photos show the progression of vinegar syndrome from small wrinkles in the emulsion at the center of the image, to the buckling of the emulsion on the right. The photos are 2005-0189 Normand Babineau Photography Collection, titled "Bahm Child"

Normand Babineau ran a small commercial photography business out of his home on Daniel Street in the late 1950's to early 1960's. He mainly photographed family events such as christenings, weddings and anniversaries. Other photography included passport photos and special events at local industries such as Playtex, Royal Bank, the Liberal convention of 1959 and Bank of Commerce functions. Mr. Babineau learned photography in the Air Force and worked for the NRC in Ottawa before moving to Arnprior.

Many of the negatives in the collection remain untouched by vinegar syndrome, but where it has broken out, it has spread to the negatives in the surrounding envelopes.

Vinegar syndrome is not 'contagious' to other materials, as it's a process that only happens to this specific film type. The only risk to the archives is the loss of the image that is undergoing this form of decay. It is also a risk to human health, as the vapours are irritating to the eyes, nose, mouth and lungs.

After the scanning project is complete, the negatives that are in bad shape (less than 10% of the collection) may need to be destroyed. This process will be carefully thought out and will occur in consultation with the family of the donor. One potential use for them could be as a teaching tool at a local university or college museum/archival studies program, in order to help show the next generation of museum and archive technicians what to look out for in the collections that they take care of.

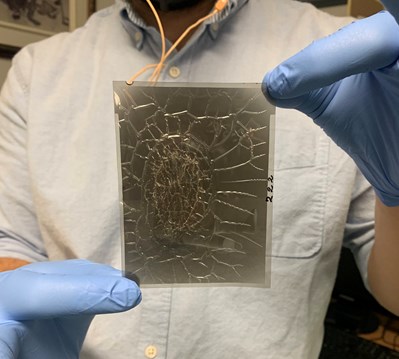

Summer Intern Marc-Alexandre Webb holds a negative that has succumbed to vinegar syndrome. The emulsion has reacted to the plastic backing of the negative and resulted in shrinking and buckling.

We are very grateful to Marc-Alexandre for his research into this phenomenon and his work to digitize and describe the negatives for preservation.

Read more about vinegar syndrome at the National Film Preservation Foundation website.

See the most recently digitized images from the Normand Babineau Photography Collection here.

Written by Emma Carey, AMBA Archivist

All About Ledgers in the Archives Archives A-Z: AMBA's April Social Media …

Earlier Posts

2023 Archives A-Z: Photography Edition

AGM Event: Archives in Your Attic!

All About Ledgers in the Archives

Inside the Vault: Vinegar Syndrome

Archives A-Z: AMBA's April Social Media Posts

Inside the Vault: Women's Institute Collections

Inside the Vault: The Handford Studio Collection

Behind the Archives' Door: The Newspaper Project

A brief history of Robert Simpson Park

Graveside Stories: Senator J. J. Greene

Graveside Stories: Lindsay's Store

Graveside Stories: Finding Kathleen

Graveside Stories: the Cameron Family